Book Review: Fatal Purity

Revolution is seen as a nasty word, with a touch of wicked pleasure. Rebel sounds with the sweet recklessness of autonomy. Revolt sings a song from freedom’s lungs. It all depends on your perspective. Language is a loose and delicate thing, easy to twist and conform according to the lips of the speaker, or the ears of the hearer.

The word revolution didn’t always have the same stigma it now carries in our modern culture. It found its roots in the word revolve – it literally just meant a turning of the wheel to something new, a change, a reformation, with an aim toward peace and respect toward governing authority whenever possible. It was completely distinct from the illegal rebellion that halos the word in blood in our minds today.

You can blame this negative stigma (among other things….) on the French if you like, because it was between the time of our revolution and theirs that the word began to change, and it was the bloodbath of French insurrection from 1789-1999, that altered its meaning entirely.

Why on earth does that matter?

Well for one thing, the French Revolution changed history, and history matters. This change was largely wrought by a short, white-wigged Frenchman who is historically described as looking like a cat, with long and narrow feline features – and a propensity for control with sharp claws dipped in blood.

His name was Maximilienon de Robespeirre.

He caused the public execution of over 17,000 men, women and children in only 4 years, with almost half of that number killed in only the last 4 months of his life.

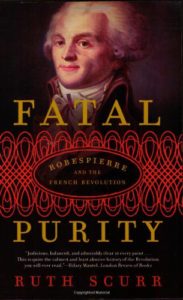

Fatal Purity by Ruth Scurr, tells of his evil, and his genius, both often misunderstood and mischaracterized.

History is a tale told largely of villains, the worst of whom, believed they were heroes. Despotism, tyranny, war, murder, all of these are, in their minds, the gruesome foundations of freedom, peace, and prosperity. The road of progress is paved with the blood of her victims. Within the ideal of the grandest utopia stands the ghost of the dystopia that sought to conceive her. Robespierre, one of the scarlet fighters for liberty, was the one that drove the fatal knife into thousands of the very people he strove to set free.

And, as with all of us, his story begins as a child. How does a child become a monster? How does innocence turn to villainy? Robespierre was a giant of history and bloodshed – but he was but a man, after all.

As Ruth Scurr begins: “The political decisions he made were influenced by the kind of person he was. No matter how complex and terrible the events, individuals – their stories, characters, and ambitions, and dreams – are always the most fascinating part of history.”

Fatal Purity is informative, significant and riveting, allowing us to gain the proper perspective on the historical proportions of this man who changed history.

Scurr continues: “There are two ways of totally misunderstanding Robespierre as a historical figure: one is to detest the man, the other is to make too much of him.”

This book strives to achieve the balance between the two.

Why Should I Read It?

Because we live like like Tevye in The Fiddler on the Roof – trying to scratch out a pleasant, simple tune, without breaking our necks. If we view Robespierre’s evil without seeing the sovereignty of God and the other effects in place, then we fall. If we view God’s sovereignty without taking into account the evil of the world we live in, and the depths of depravity to which our good intentions can carry us, then we fall. So we must gain an accurate perspective on history.

And we must gain a proper perspective of ourselves. Of man. Of the world in which we live. We must see where our hearts carry us when God is not in them. We must see how we strive to satisfy our pleasures and desires when we refuse the only One who can.

“It is the pictures in Robespierre’s mind that are the key to his story,” Scurr explains. “Two of them are more vivid than any of the others: his picture of an ideal society and his picture of himself. The Revolution superimposed the two and he believed, to the point of insanity, that he was the instrument of Providence, charged with delivering France to her exalted future. If the French were not yet worthy of such a future, it was clear to him that they must be regenerated – through virtue or terror – until they became what destiny demanded of them.”

Robespierre strove to create a future exalted around himself, and ended, instead, in giving himself to the horrendous wake of its failure, his life taken by the very people he had tried to save. He believed destiny demanded something of him – that destiny was, in effect, himself. In the end, he found the true destiny of those who fail to believe in Christ, and it was very different from the eternal destiny of true freedom – a freedom Robespierre lived and killed and died endeavoring to taste.